The Beginning of Machine Communication

The interplay between human communication and machine computation has been changing drastically for the last hundred years, but the pace has recently accelerated with the first serious contender for a natural language-user other than human beings: the new generation of Large Language Models (LLMs) that have found their way into academic research and deployed product alike.

Having a computational model that can wield language, still very imperfectly, is changing the conceptual models we use to think about machine learning models in general.

Models that work with language have traditionally been viewed from the functional perspective: a function ƒ (a trained model) that maps an input x (a prompt) to an output y (a response). Of course, anything can be described as a series of function applications, but such a framework tends to suggest a specific perspective: that machines are predictable and regular in ways that organic phenomena are not. While our LLMs can still be described as functions, their ability to interact with humans via dialogue has upgraded the metaphors used to talk about LLMs to ‘agents’ and ‘collaborators’. These new metaphors are not always accurate, but they do suggest that we should be studying what happens when humans and machines coordinate over multiple interactions, the way humans coordinate with each other in everyday life.

Similarly, the study of the computational manipulation of language has been described by the term ‘Natural Language Processing’—a term that points to the implicit metaphor of processing language like an industrial product for some definite, standardized end. This doesn’t seem to be how we think about language models. Instead, we seem to be able to do a basic kind of coordination with them, and we tend to evaluate their ability to do what we want them to do according to their ability to coordinate with us through language. It is the beginning of Machine Communication.

Coordination vs. Simulation

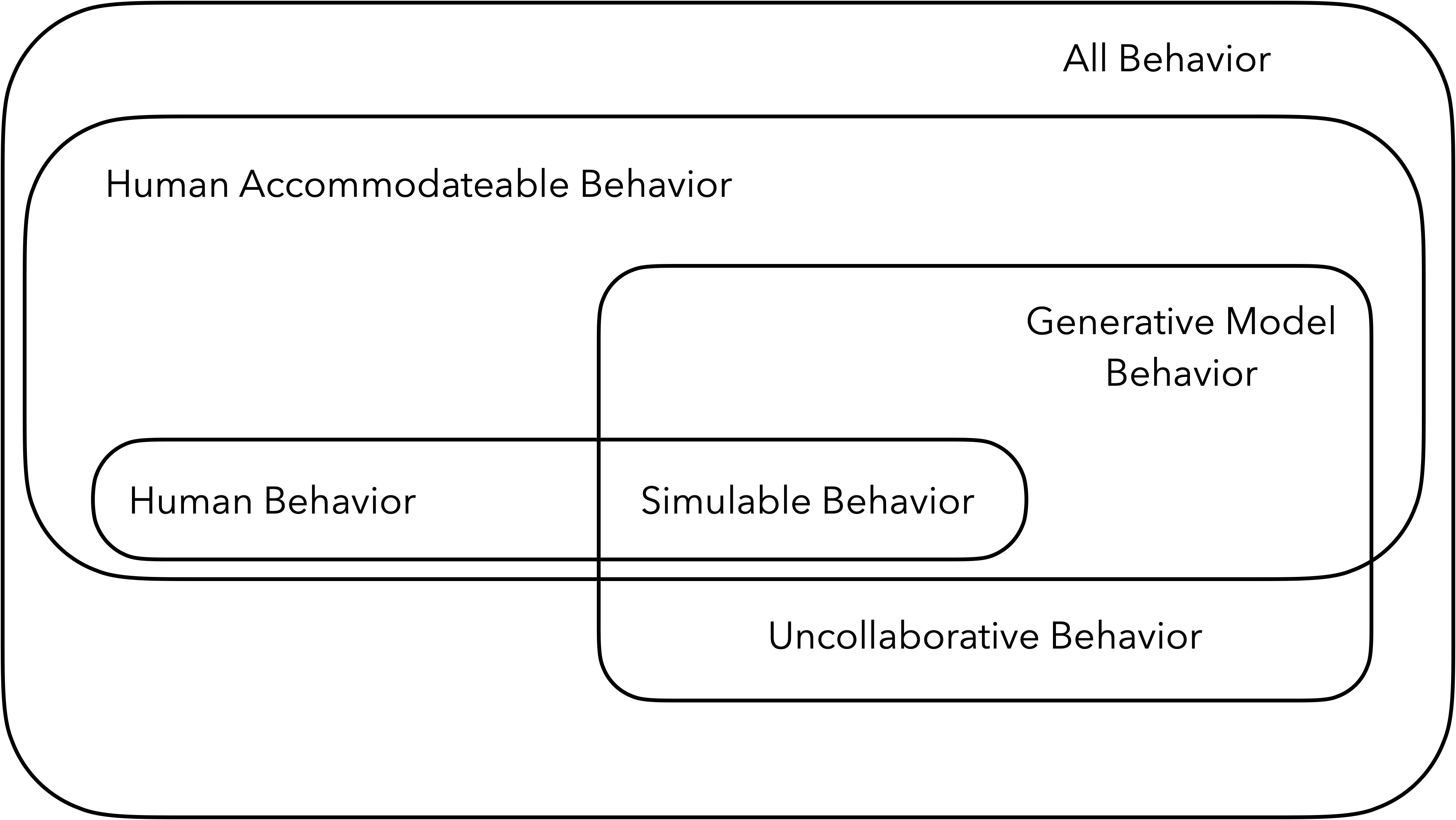

Figure 1: A diagram representing different kinds of behaviors that humans and generative models display.

Figure 1: A diagram representing different kinds of behaviors that humans and generative models display.

In the past much of ‘Artificial Intelligence’ was framed as trying to get machines to do what humans do so easily, to complement machines’ ability to do repetitive, precise tasks. Trying to simulate humans has often led to mixed results, especially since the mechanisms by which machines produce human like behavior is often different by necessity.

Perhaps direct simulation of humans, and trying to measure it, is missing the point: LLMs and other generative models can take natural language input from normal humans, but also have the ability to do things that most humans can’t do, such as pass high-level exams such as the Bar (Katz et al. 2023) or generate paintings across a range of styles that most humans would struggle to cover.

As generative models improve, it becomes possible to explore not just human behavior, but what kind of behavior humans can make use of, but could never produce on their own: human accomodateable behavior. In doing this, we also end-up exploring what kind of behavior humans can’t contend with, uncollaborative behavior produced by models that don’t properly capture what it means to work with humans. This back and forth can allow us to explore a new question: What kinds of cooperation humans want that have been difficult or impossible to setup before machines were capable of more organic communication?

How can we ‘see’ coordination?

A problem arises when trying to study something as abstract as communication or coordination: we can generally only see the surface-level form of communication (the words someone literally said) and not what was understood by the different parties (the actual substance of communication), which often leads to hidden assumptions about what the observable says about the unobservable.

This happens wherever we lack a method for measuring precisely what we want to study. For instance, there used to be a question in one corner of biology: How do bats avoid collisions when they’re all emerging from their cave by the thousands? Researchers took high speed cameras to bat caves and found a very simple answer: they don’t avoid collisions. Bats run into each other all the time. It was the assumption of the researchers that, because bats were largely not found lying dead on the ground, there were very few collisions—the hidden assumption being the collisions must lead to fatalities, rather than being handled elegantly when they occur.

Figure 2: Biologists taking high-speed photographs of bats emerging from their cave. From Lens of Time: Bat Ballet produced by Spine Films.

Figure 2: Biologists taking high-speed photographs of bats emerging from their cave. From Lens of Time: Bat Ballet produced by Spine Films.

In studying how machines can communicate with humans using natural language (and even with each other), we run a similar risk: assuming that machines are good at doing something because they avoid an expected failure mode that humans have. Yet machines, have a wonderful advantage as an object of study: because we have perfect, mechanical representations of how computational models operate we can directly study how machines produce the language they do in various situations, and how that language would change given a slightly different situation, or even a slightly different machine. We can causally (and casually) perturb machine communication in a way that is impossible to do with humans directly.

What new questions are worth asking?

Prior to neural models of language, systems where humans communicate information to machines or vice versa required formal protocols (such as programming languages) to allow machines to deal with the complexities of organic human communication. With the rise of LLMs, humans can type messages to machines the way they do each other, with machines able to coordinate among themselves in human auditable language, and then articulate the result to humans in their native communication channel: natural language. Rather than programming a system to do easily formalizable tasks, we are seeing the beginning of discussing tasks that can be delegated to a network of people and machines—with the help of machines, to coordinate the process.

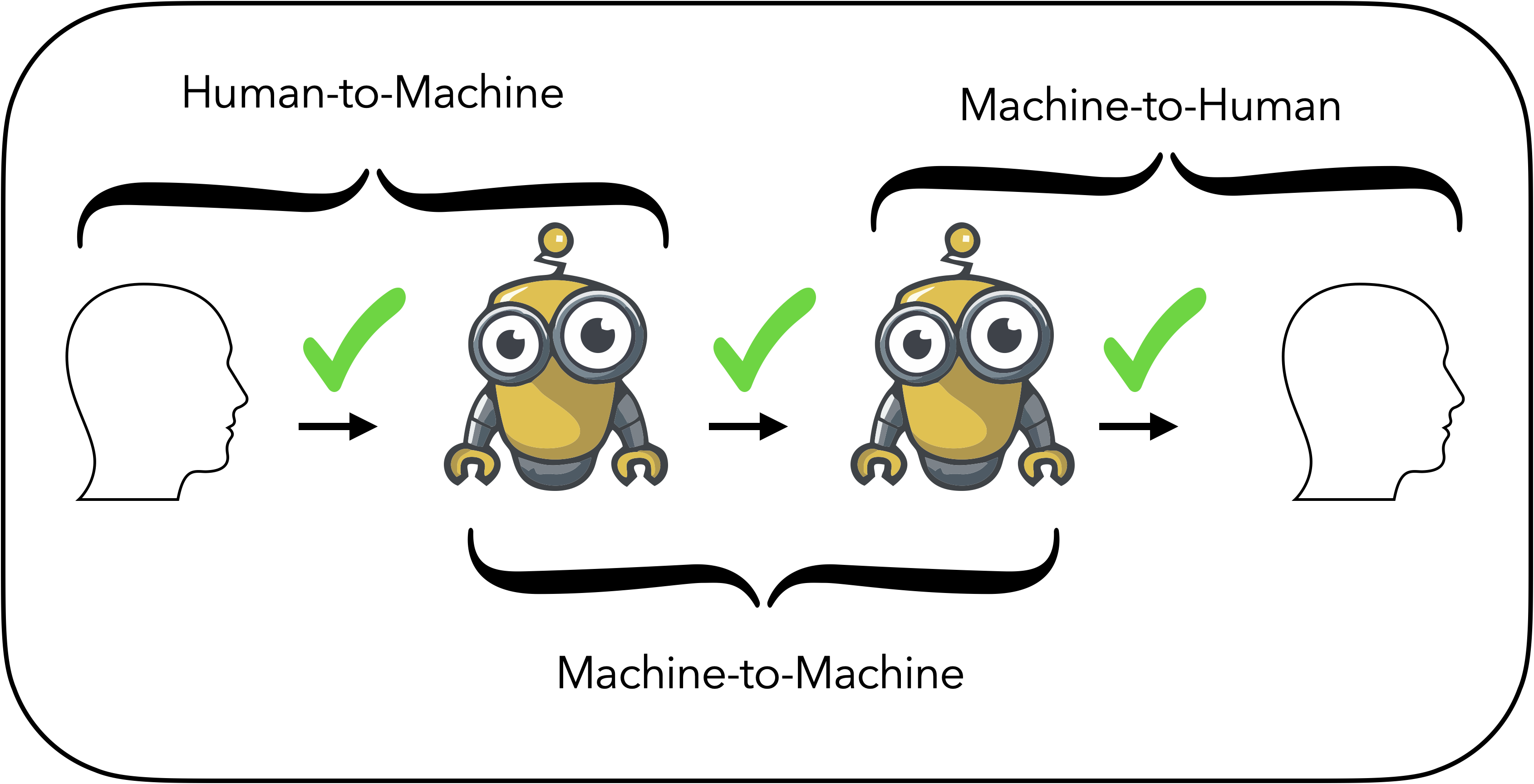

Figure 3: Three kinds of communication: (1) Human-to-machine communication where a human hands off a task to a machine (2) Machine-to-machine communication where different machines coordinate with each other to solve a task and (3) Machine-to-human communication has become increasingly common with LLMs.

Figure 3: Three kinds of communication: (1) Human-to-machine communication where a human hands off a task to a machine (2) Machine-to-machine communication where different machines coordinate with each other to solve a task and (3) Machine-to-human communication has become increasingly common with LLMs.

While software has allowed people to process data and communicate with each other in new ways, people were still generally required for coordination that can’t be described by relatively simple rules. With machines now capable of gracefully accepting natural language as an input and producing it as an output, we can easily study communication within heterogeneous networks of humans and machines.

We may begin to invent better ways to organize complex and even creative task among a large number of agents, and we may further be able to ask: What were the strategies humans had been using previously, that we found so difficult to formalize before we had machines to compare them to?

Cited Works

Spine Films. 2016. “Lens of Time: Bat Ballet.” bioGraphic. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.biographic.com/lens-of-time-bat-ballet/.

Katz, Daniel Martin, Michael James Bommarito, Shang Gao, and Pablo Arredondo. 2023. “GPT-4 Passes the Bar Exam.” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4389233.